On Failure in Metallic Materials

As a continuation of my series on composite materials and health monitoring, I wanted to talk about failure in composites. In writing it, I decided that first I needed to talk about failure in metallic materials. In writing that, it turned out that it was long enough to be a separate post by itself. So here it is, a small primer on failure, especially in metallic materials.

We’ll talk about composites next time.

What exactly is "failure"?

A component is said to have failed when it can no longer perform the task that it was designed for. Failure does not necessarily mean breaking, although sometimes it might. Failure in an engineering sense has as much to do with “what the designer intended” as with “the physical structure itself”.

For example, a bridge may be getting old and developing some cracks here and there. At what point do you say that the bridge is “unsafe for use”? The design and engineering teams set up some criteria to evaluate the structure. For example, they might say that “any cracks detected must not be greater than so-and-so length”. This does not mean that the bridge is going to break apart when a crack of that so-and-so length appears. It just means that the engineers are no longer satisfied with how the bridge may hold up in the future. Hence, the bridge component that developed the big-enough crack will be said to have failed.

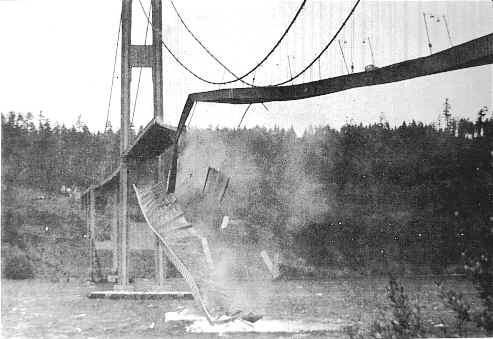

Tacoma Narrows Bridge. (Source)

If the above paragraph seems to convey unnecessary caution on the part of the engineer (why call the bridge unsafe if it isn’t breaking up?), consider that a bunch of reasons go into making such decisions. As an example, the engineers may consider their ability to detect every crack. The engineering team may consider the possibility that they could not detect some defects. What is the probability of a serious defect not being detected?

And there’s good reason to be cautious – if they get it wrong, bridges do collapse.

How do metallic materials fail?

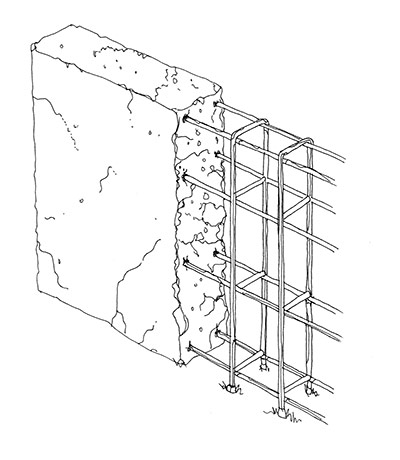

In the previous section, we have been talking about cracks. Here’s why they form in the first place. Cracks form when the load on a given region of a component (i.e. stress, = force per unit area) becomes higher than what the material can handle. This may be because an unexpected amount of load was put on the structure that it was never designed for. It may also be that the capacity of the structure to withstand stresses has diminished over time as the component has aged. In any case, when the stress is too much for the component to bear, the component fractures and develops a crack. The particular mechanics of the fracture itself is a vast area of study in itself, and is way beyond the scope of this piece. Suffice to say, that crack formation weakens the component, and the larger the crack gets, the worse in condition the component becomes. Ultimately, the crack will grow large enough that the component will break into two, and will be unable to take any load at all.

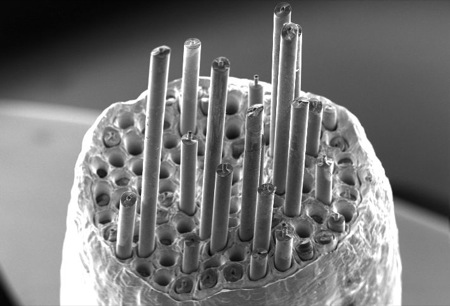

Crack propagation under certain conditions. (Source)

For metallic components, since the material itself is nominally homogenous (nominally, because nothing can be perfectly homogenous, but for all intents homogeneity may be assumed), the crack that ultimately causes the material to fail usually occurs where the stress happens to be the greatest. Further, as I mentioned above, the formation of a crack weakens the material, and so once a crack does form, any further worsening in that region accumulates around the same crack (weak zone) instead of creating new cracks all the time. “Where the stress is greatest” usually depends on the geometry of the component, on how the loads are distributed, and, indeed, on tiny variations in the homogeneity of the material itself.

Crack propagation in glass shot at extremely high frame rate. (Source)

For metals, therefore, the mantra for evaluating the component may be condensed as: “follow the cracks”. Wherever a crack seems to be worsening, is where final failure will most likely occur.

That’s it for today’s discussion on crack propagation; next time we’ll get to what I had actually set out to discuss – failure in composites.